Taming Symmetry: A Dive into Lie Groups with Python

Expertise Level ⭐⭐⭐⭐

Lie groups play a crucial role in Geometric Deep Learning by modeling symmetries such as rotation, translation, and scaling. This enables non-linear models to generalize effectively for tasks like object detection and transformations in generative models.

This article leverages the Python Geomstats, introduced in a previous article Overview of Geomstats for Geometric Learning

🎯 Why this Matters

Purpose: Identifying symmetries in datasets and models is essential for analyzing complex problems and simplifying deep learning architectures.

Audience: Data scientists and engineers curious about Lie groups and their applications in machine learning.

Value: Develop practical expertise in Lie groups and Lie algebras through hands-on exploration of the 3-dimensional Special Orthogonal (SO3) and Special Euclidean (SE3) groups.

🎨 Modeling & Design Principles

Quest for Symmetry

Symmetry is the organizing principle behind geometric deep learning. It tells you what should not change (invariance) or how things should change (equivariance) when you transform the input

The terms symmetry, invariance and equivariance can be confusing.

Symmetry (Webster dictionary): The property of remaining invariant under certain changes (as of orientation in space, of the sign of the electric charge, of parity, or of the direction of time flow) —used of physical phenomena and of equations describing them

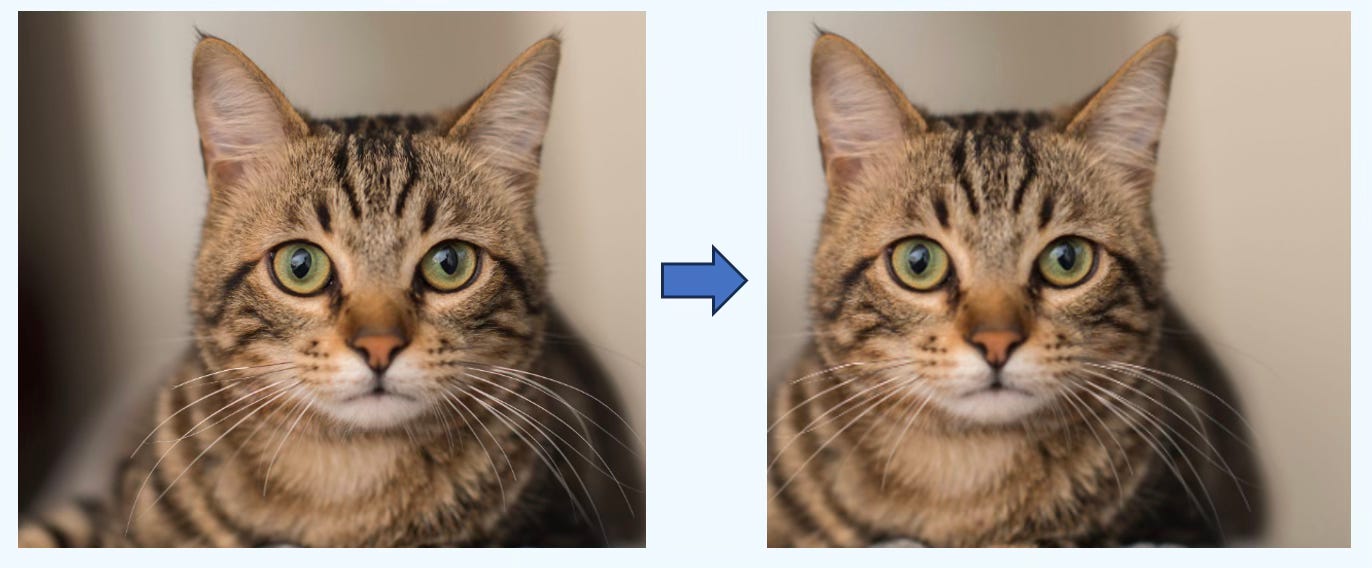

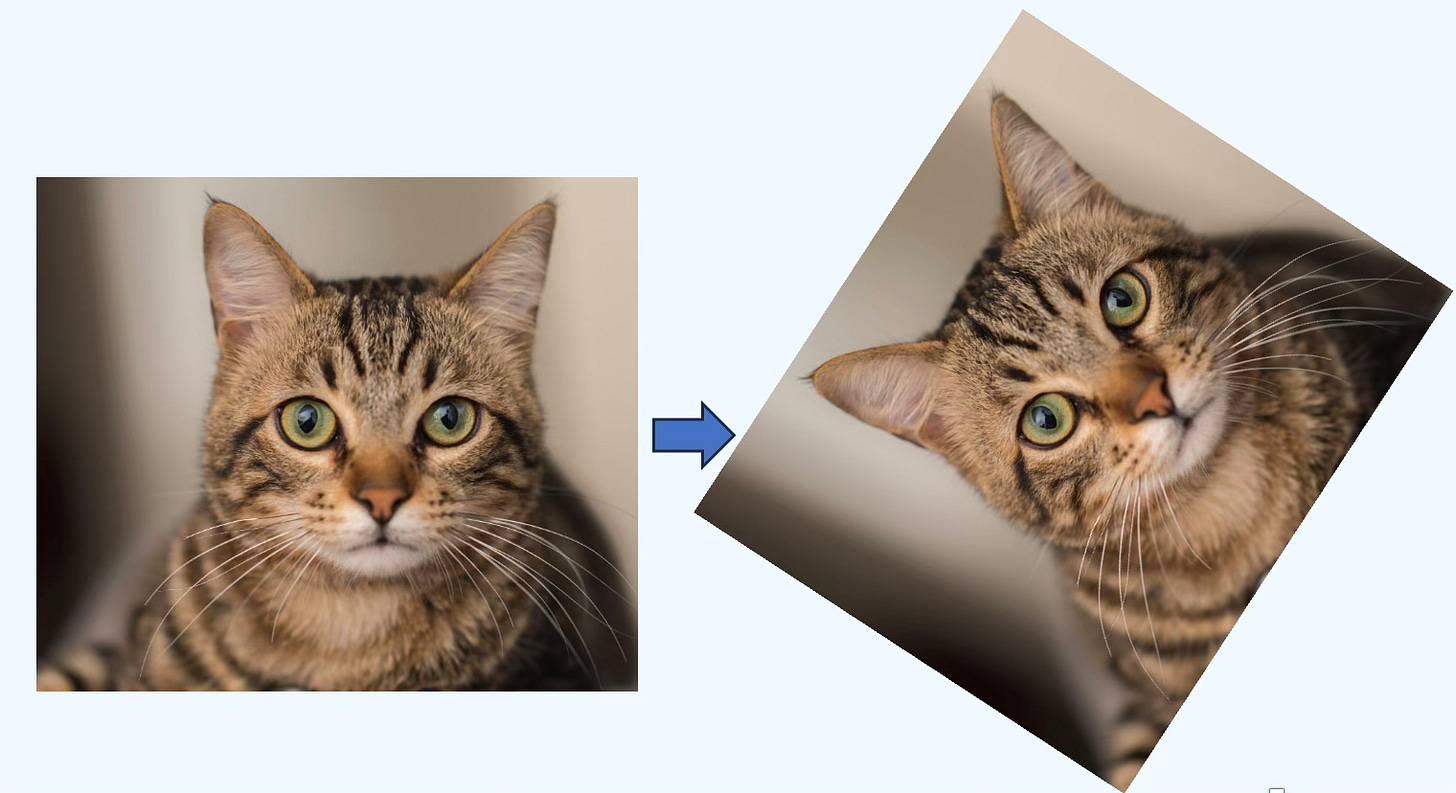

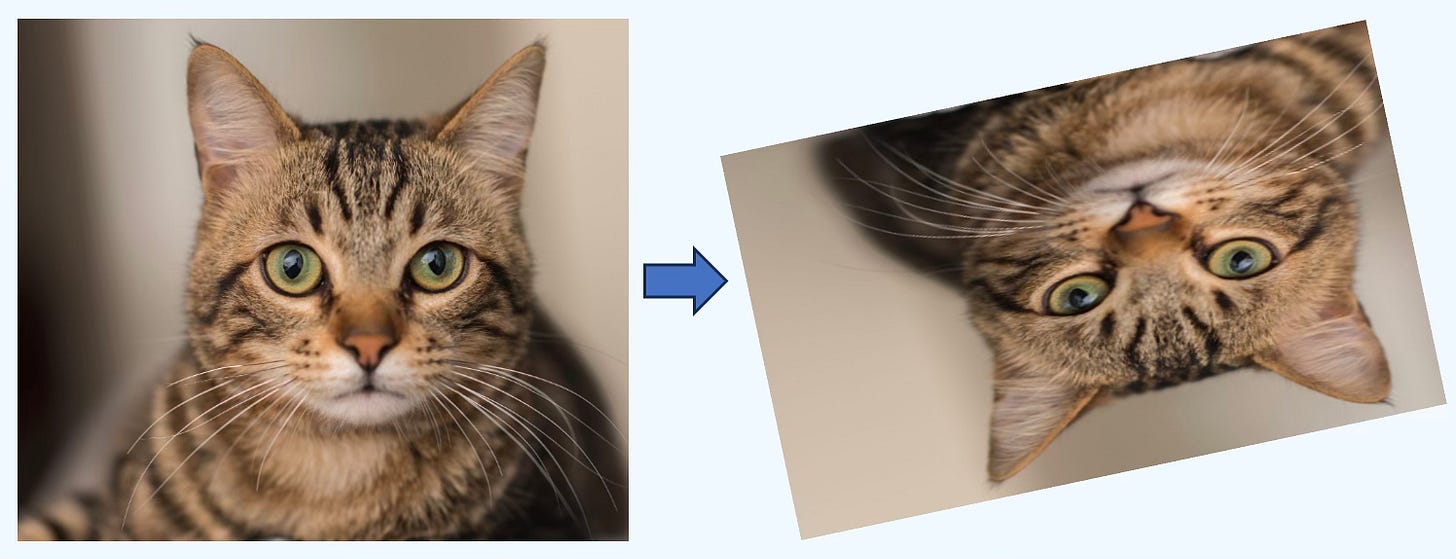

Invariance: The output doesn’t change when the input is transformed. Example: a cat classifier still predicts “cat” for an upside-down photo.

Equivariance: The output changes in a predictable way under the same transformation. Example: rotate an image, and the predicted segmentation mask rotates accordingly.

The concept of symmetry and invariance can be easily illustrated in the context of computer vision. Vision models are often trained to be invariant to common geometric transforms:

Translation: horizontal/vertical shifts; the object is recognized regardless of image location.

Rotation: turning the image by some angle.

Scaling: resizing the object.

Affine transforms: compositions of translation, rotation, scaling, and shear; they preserve straightness and parallel lines.

Introduction to Lie Groups

I highly recommend that readers unfamiliar with the fundamental concepts of differential geometry and their significance in Geometric Deep Learning explore Introduction to Geometric Deep Learning [ref 1]

Lie groups are mathematical structures that combine the properties of groups and smooth manifolds, meaning they support both algebraic and differentiable operations. Named after the Norwegian mathematician Sophus Lie, these groups play a fundamental role in continuous symmetries, particularly in physics and geometry.

A Lie algebra is the tangent space at the identity element of a Lie group, equipped with a special operation called the Lie bracket, which encodes the infinitesimal structure of the group.

⚠️ A thorough tutorial and explanation of Lie groups, Lie algebras, and geometric priors for deep learning models is beyond the scope of this article. Instead, the following sections concentrate on experiments involving key elements and operations on Lie groups using the Geomstats Python library.

Key Properties:

Continuity and Differentiability: Lie groups are differentiable manifolds, allowing the application of calculus.

Group Structure: They satisfy closure, associativity, identity, and inverse properties.

Infinitesimal Generators: The corresponding Lie algebra describes local (infinitesimal) symmetries, making them useful for transformations.

Applicability to Machine Learning

Lie groups provide a powerful mathematical framework for encoding symmetry, invariance, and geometric structure in machine learning models.

Data Augmentation & Invariance

Many datasets exhibit symmetries (e.g., images are invariant to rotations and translations).

Lie groups help define equivariant neural networks that maintain these symmetries.

Geometric Deep Learning

Lie groups are used in manifold learning, graph neural networks (GNNs), and generative models to impose structured constraints. (i.g., SE(3)-equivariant networks in molecular modeling respect 3D rotational and translational symmetry).

Optimization & Lie Algebra Representations

Optimization problems in deep learning can be formulated on Lie groups (e.g., in Riemannian optimization, where parameters evolve on curved manifolds).

The exponential and logarithm maps of Lie groups facilitate structured gradient-based learning.

Physics-Inspired AI

In reinforcement learning and robotics, Lie groups model rigid body motion essential to robots’ perception and control.

Smooth Manifolds

📌📌 I highly recommend readers to get acquainted with manifolds to browse through two previous articles

Let’ start with a brief review of the key mathematical concepts behind the Lie groups:

Differential geometry is an extensive and intricate area that exceeds what can be covered in a single article or blog post. There are numerous outstanding publications, papers and tutorials [ref 2, 3, 4] that provide foundational knowledge in differential geometry and tensor calculus, catering to both beginners and experts.

A manifold is a topological space that, around any given point, closely resembles Euclidean space. Specifically, an n-dimensional manifold is a topological space where each point is part of a neighborhood that is homeomorphic to an open subset of n-dimensional Euclidean space. Examples of manifolds include one-dimensional circles, two-dimensional planes and spheres, and the four-dimensional space-time used in general relativity.

A smooth (or differential) manifold is a topological space that locally resembles Euclidean space and allows for smooth (infinitely differentiable) transitions between local coordinate systems. This structure allows for the use of calculus on the manifold.

A Riemannian manifold is a smooth manifold that comes with a metric tensor, providing a way to measure distances and angles.

The tangent space at a point on a manifold is the set of tangent vectors at that point, like a line tangent to a circle or a plane tangent to a surface.

Tangent vectors can act as directional derivatives, where you can apply specific formulas to characterize these derivatives.

A geodesic is the shortest path (arc) between two points in a Riemannian manifold.

Exponential & Logarithm Maps

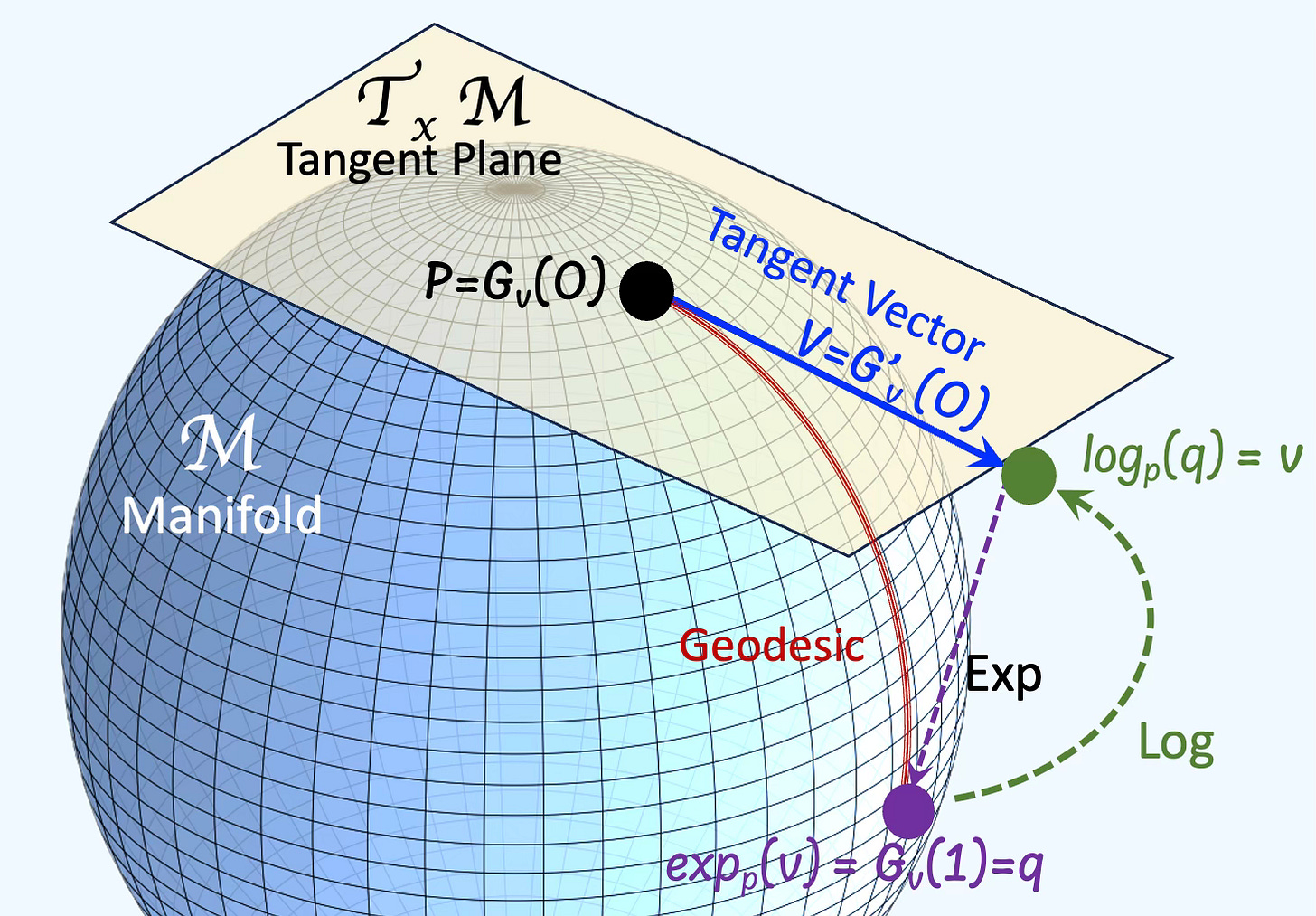

Given a Riemannian manifold M and a tangent space TM, an exponential map is a map from a subset of a tangent space of a Riemannian manifold. Given a tangent vector v at a point p on a manifold, there is a unique geodesic Gv that satisfy Gv(0)=p and G’v(0)=v. The exponential map is defined as expp(v)= Gv(1)

For the same Riemannian manifold, given a geodesic Gv starting at point p with a direction v., the logarithm map is defined as

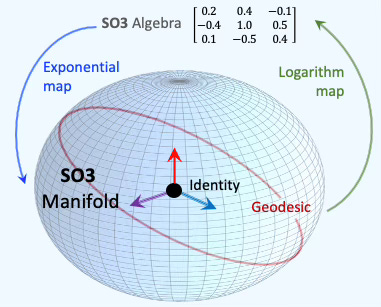

The exponential and logarithm maps are illustrated below:

Fig. 1 Manifold with tangent space and exponential/logarithm maps

⚠️. Lie groups do not resemble spheres or hyperspheres, but we use them here purely for illustrative purposes.

Lie Groups

Lie groups play a crucial role in Geometric Deep Learning by modeling symmetries such as rotation, translation, and scaling.

In differential geometry, a Lie group is a mathematical structure that combines the properties of both a group and a smooth manifold. It allows for the application of both algebraic and geometric techniques. As a group, it has an operation (like multiplication) that satisfies certain axioms (closure, associativity, identity, and invertibility) [ref 5, 6].

A 'real' Lie group is a set G with two structures: G is a group and G is a (smooth, real) manifold. These structures agree in the following sense multiplication (a.k.a. product or composition) and inversion are smooth maps.

A morphism of Lie groups is a smooth map which also preserves the group operation:

Example of Lie Groups

Here are some commonly used Lie groups.

General Linear Group of invertible matrices

The General Linear Group, denoted as GL(n,R) (or GL(n,C) for complex values) is the set of all invertible n×n matrices with real entries, equipped with matrix multiplication as the group operation. It is a Lie group because it forms a smooth differentiable manifold and supports continuous transformations.

Symmetric Positive Definite Group

The Symmetric Positive Definite (SPD) Group, denoted as SPD(n), is the Lie group of all n×n real symmetric positive definite matrices. It plays a crucial role in statistics, machine learning, optimization, and Riemannian geometry.

[1] Specifies the symmetry condition

[2] Ensures the positive definite condition

Special Orthogonal Group

The Special Orthogonal Groups SO(2) (resp. SO(3)) are the Lie groups that represents rotations in 2-dimensional (resp. 3-dimensional) space. It is widely used in robotics, physics, computer vision, and geometric deep learning to describe rigid body rotationswithout scaling or reflection.

[1] Enforces orthogonally for which the 2 or 3 unit of rotations are mutually perpendicular

[2] Ensures rotation and preserves orientation

Special Euclidean Group

The Euclidean group is a subset of the broader affine transformation group. It contains the translational and orthogonal groups as subgroups. The Special Euclidean Group is a subgroup of Euclidean group. Any element of SE(n) can be represented as a combination of a translation and an orthogonal transformation, where the translation B can either precede or follow the orthogonal transformation A.

In robotics and physics, an element of SE(3) is often referred to as a rigid transformation, since it describes a rotation + translation without scaling or deformation.

An element is represented as a 4×4 homogeneous transformation matrix for which R is a SO(3) rotation matrix and t is a 3-dimensional translation vector.

Lie Algebras

Lie algebra can be viewed as the tangent space to the Lie group at the identity. Lie algebra can be viewed as the tangent space to the Lie group at the identity which linearize the group element near the identity.

For example, the group SO(n) of rotations is the group of orientation-preserving isometries of the Euclidean space. The Lie algebra so(n, R) consisting of real skew symmetric n × n matrices is the corresponding set of infinitesimal rotations.

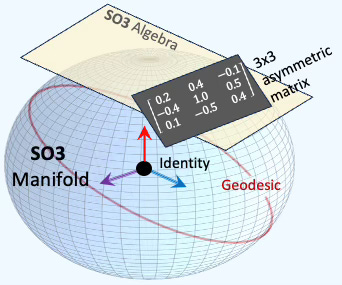

Fig. 2 Visualization of SO3 Lie groups and its algebra of 3x3 skewed asymmetric matrices

⚠️ Visualizing the SO(3) manifold in three dimensions is inherently challenging. In this example, we represent the space of rotations as a solid ball, where the center corresponds to the identity rotation and each point within the ball encodes a rotation using the axis-angle representation. Reference SO(3) Visualization

Theoretically, a Lie algebra is a mathematical structure used to study continuous symmetries, consisting of a vector space equipped with a bilinear operation called the Lie bracket, which satisfies

antisymmetry ([X,Y]=−[Y,X][X,Y]=−[Y,X])

Jacobi identity ([X,[Y,Z]]+[Y,[Z,X]]+[Z,[X,Y]]=0[X,[Y,Z]]+[Y,[Z,X]]+[Z,[X,Y]]=0).

The Lie bracket deserves a lengthly analysis and will be described in a future article.

📌 The terminology used for Lie groups and Lie algebras can sometimes be confusing, as it differs from traditional differential geometry definitions.

The identity element is often used instead of the base point in differential geometry.

A group element in Lie theory corresponds to what is traditionally called a point on the manifold.

An element of the Lie algebra corresponds to a tangent vector

This article adheres to the semi-official Lie group terminology for consistency.

Geomstats

Geomstats is a free, open-source Python library designed for conducting machine learning on data lying on nonlinear manifolds, an area known as Geometric Learning.

The core concept of Geomstats is to incorporate differential geometry principles, such as manifolds and Lie groups, into the development of statistical and machine learning models. This open-source, object-oriented library follows Scikit-Learn’s API conventions for seamless integration [ref 7, 8].

Geomstats serves as a practical tool for gaining hands-on experience with geometric learning fundamentals while also supporting future research in the field.

The Geomstats library is described in detail in the following article Overview of Geomstats for Geometric Learning of this newsletter.

⚙️ Hands-on with Python

This article emphasizes the practical applications of Lie theory. As such, this section explores two commonly used Lie groups: SO(3) and SE(3).

Environment

Libraries: Python 3.12, Geomstats 2.8.0

Source code: Github.com/geometriclearning/geometry/lie

To enhance the readability of the algorithm implementations, we have omitted non-essential code elements like error checking, comments, exceptions, validation of class and method arguments, scoping qualifiers, and import statements.

🔎 Special Orthogonal Group

The Special Orthogonal Group SO(3) is the Lie group that represents rotations in 3-dimensional space. It is widely used in robotics, physics, computer vision, and geometric deep learning to describe rigid body rotations without scaling or reflection.

📌 The term ‘Special’ refers to the fact that SO(3) is actually a subgroup of Orthogonal matrices with a relaxed condition det(R) +/- 1

The Lie algebra of SO(3) is defined as group of skew-symmetric 3x3 matrices A:

Any skew-symmetric 3x3 matrix in Lie algebra can be defined as a linear combination of the following 3 fundamental generators of rotations about x, y and z axes:

📌 Convention: Elements of Lie Algebra are written with the Fracktur font

⏭️ This section guides you through the design and code.

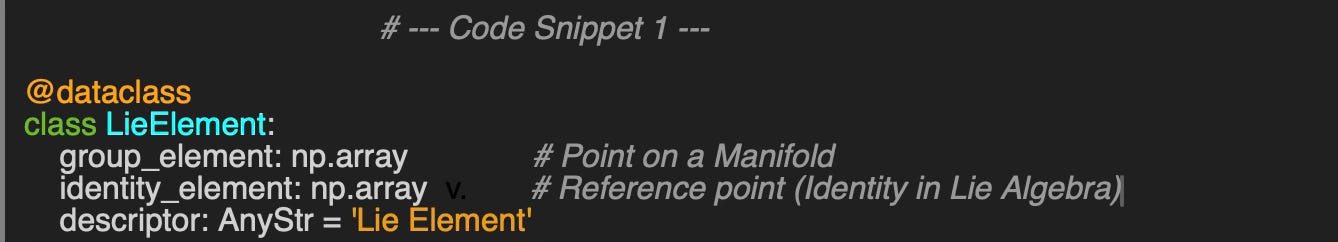

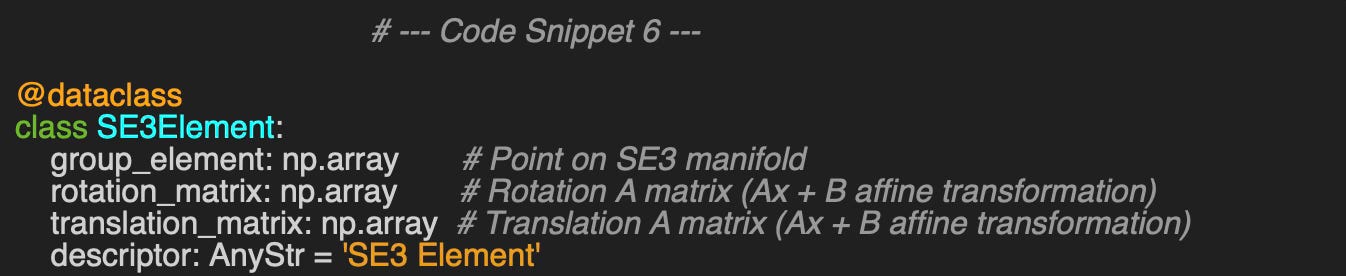

First let’s define a structure, LieElement, to define an element of the SO3 group with the following attributes:

group_element as a Numpy array representing a data point on the manifold

identity_element as the reference point for the tangent space and Lie algebra

descriptor as an optional description of the Lie element for visualization purpose

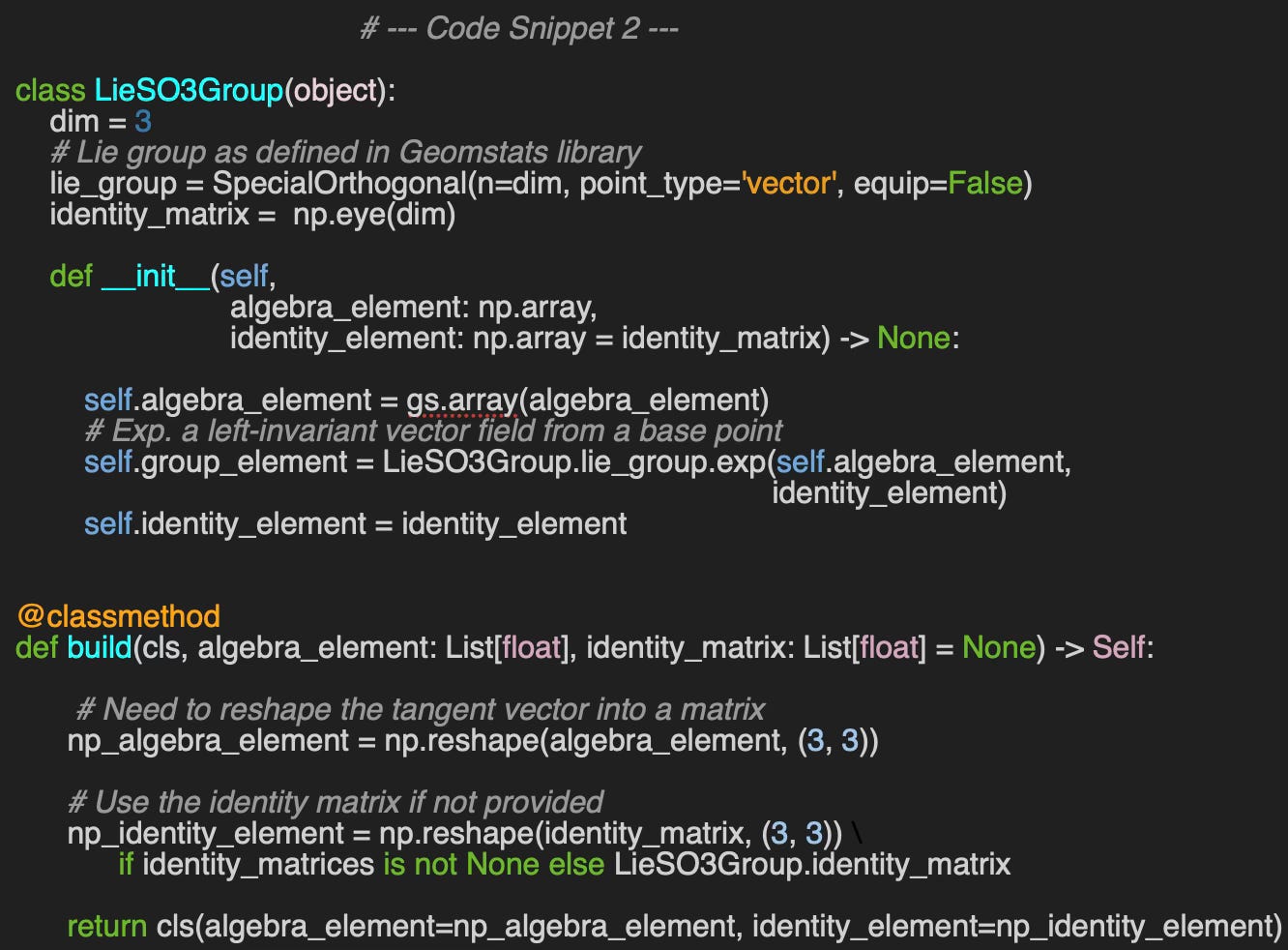

Next we wrap the creation and manipulation of elements of the SO(3) into a class LieSO3Group with two constructors:

__init__: Default constructor that create a new element in the SO3 manifold, group_element, using the element in Lie Algebra (3x3 rotation matrix) algebra_element and a reference point , identity_element.

build: Alternative constructor for which the parameters are the vector as a 9 float values list and an array representing the identity matrix if defined.

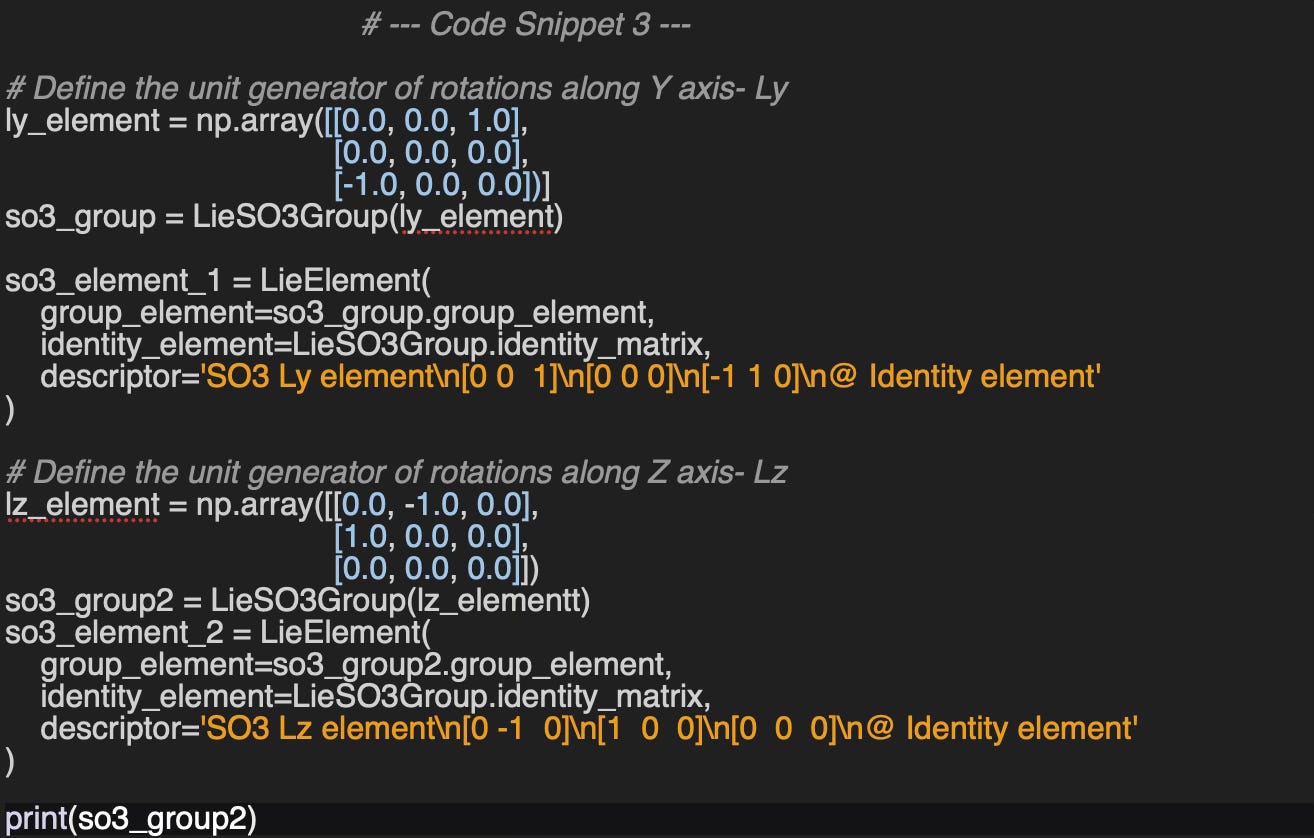

We use the constructors of the LieSO3Group class to generate two points on the SO3 manifold, so3_element_1 and so3_element_2. These points are represented as vectors in 3-dimensional Euclidean space for visualization purposes.

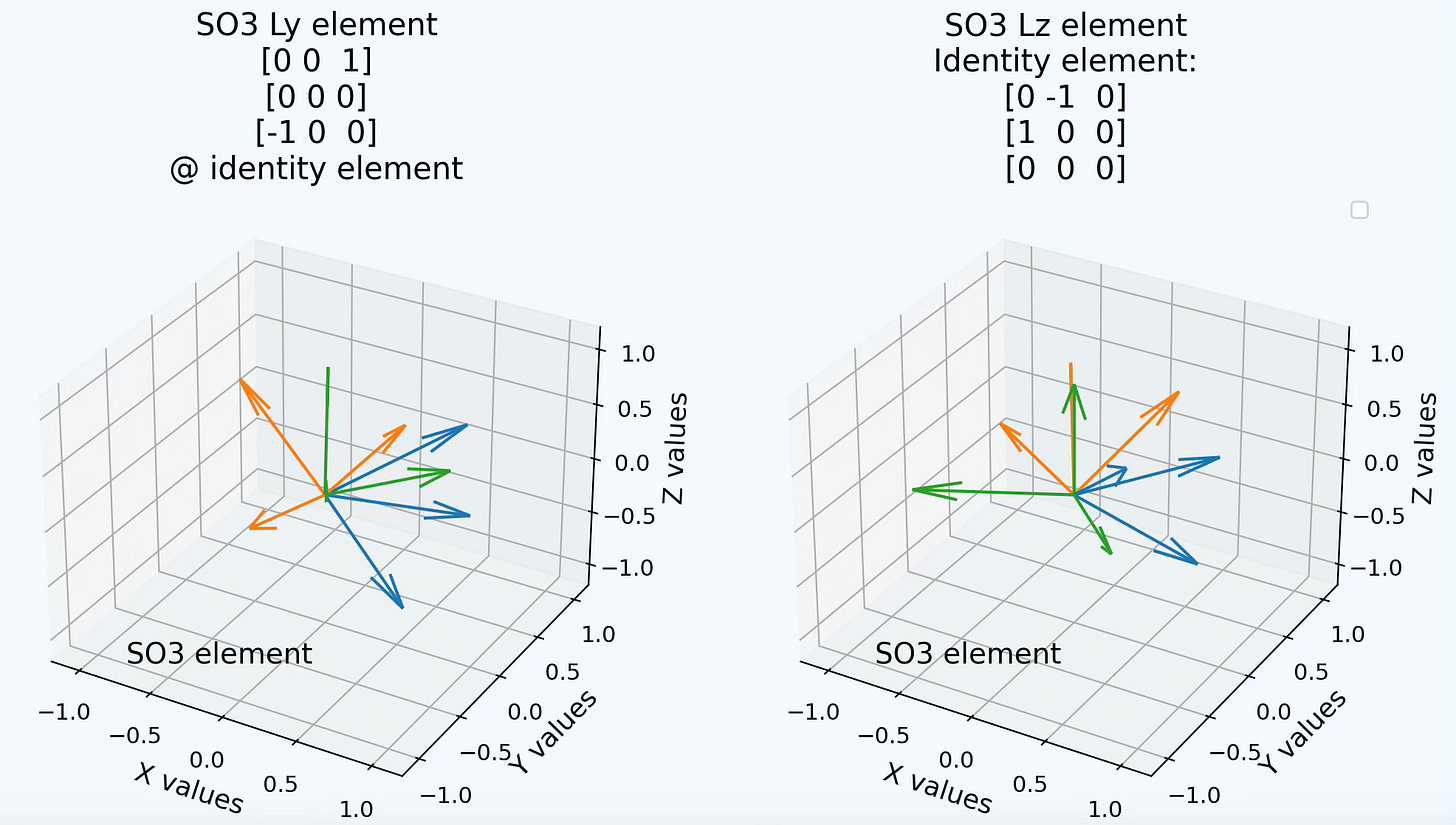

The first SO3 element uses the identity as the reference for a fundamental generator of rotations around Y axis: Ly= [[ 1. 0. 0.] [ 0. 0. -1.] [ 0. 0. 0.]]

The second SO3 element uses the same reference for a fundamental generator of rotations around Z axis: Lz= [[ 0. -1. 0.] [ 1. 0. 0.] [ 0. 0. 0.]]

Output for so3_group2

Algebra element:

[[ 0. -1. 0.]

[ 1. 0. 0.]

[ 0. 0. 0.]]

SO3 group element:

[[ 9.19666190e-01 -9.97270378e-01 -3.85335888e-17]

[ 9.97270378e-01 9.19666190e-01 -3.85335888e-17]

[ 0.00000000e+00 0.00000000e+00 1.00000000e+00]]Let’s visualize the SO3 group element corresponding to the two algebra elements Ly and Lz

Fig. 3 Visualization of SO3 group element for Ly and Lz unit at identity

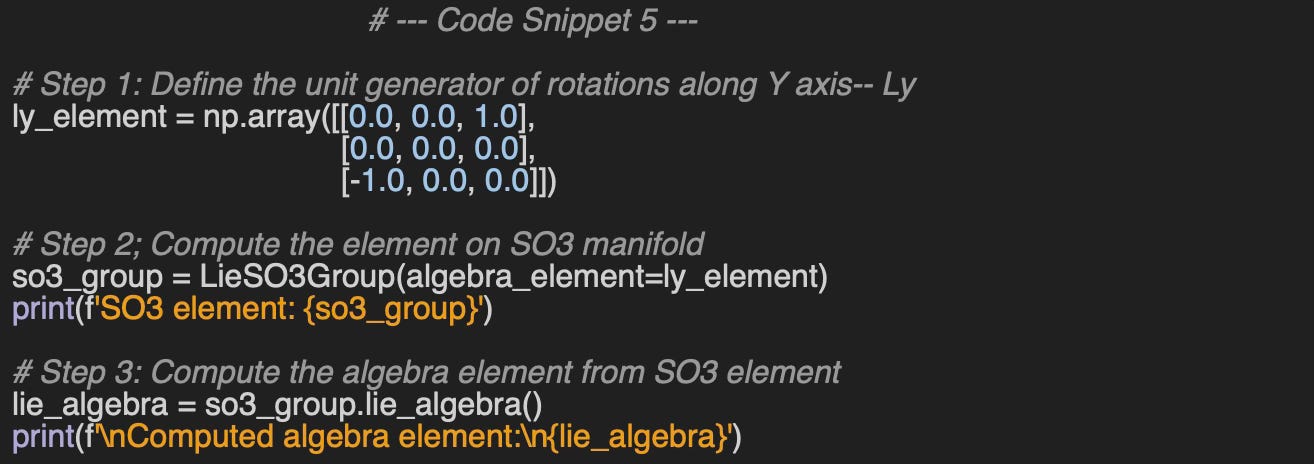

It would be insightful to verify the computation of a Lie algebra element from an SO(3) group element using the logarithm map. The validation process involves the following steps:

Generate an SO(3) group element by applying the exponential map to a rotation in the tangent space (Lie algebra).

Retrieve the corresponding Lie algebra element from the computed SO(3) group element using the logarithm map.

Compare the extracted Lie algebra element with the original rotation matrix to assess the accuracy of the computation.

This 3-step process is illustrated below

Fig. 4 Visualization of validation of the computation of exponential and logarithm maps (Algebra → [Exp] →Group →[Log]→ Algebra)

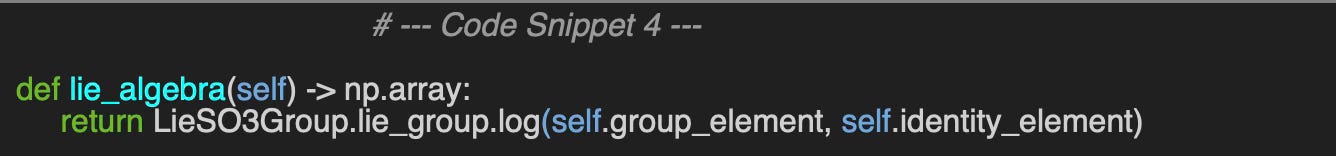

First let’s implement the computation of an algebra element from an existing SO3 group element.

The method utilizes the implementation of the logarithm map, log in the Geomstats library.

Output:

Algebra element:

[[ 0. 0. 1.]

[ 0. 0. 0.]

[-1. 0. 0.]]

SO3 group element:

[[ 9.19666190e-01 0.00000000e+00 9.97270378e-01]

[ 0.00000000e+00 1.00000000e+00 0.00000000e+00]

[-9.97270378e-01 -3.85335888e-17 9.19666190e-01]]

Computed algebra element:

[[ 3.25136469e-17 0.00000000e+00 1.00000000e+00]

[ 0.00000000e+00 0.00000000e+00 0.00000000e+00]

[-1.00000000e+00 -5.55111512e-17 1.62568234e-17]]As we can see, the computed algebra element is equal (+/- rounding error) to the original rotation Ly.

🔎 Special Euclidean Group

⏭️ This section guides you through the design and code.

The special Euclidean group, SE(3) is a group of Euclidean transformations that represent rigid motions.

As with SO3 group, we define an element on SE3 group of type SE3lement with the following attribute

group_element as a Numpy array representing a data point on the manifold

rotation_matrix as the rotation matrix component of the affine transformation in the Lie algebra

translation_matrix as the translation component of the affine transformation in the Lie algebra

descriptor as an optional description of the Lie element for visualization purpose

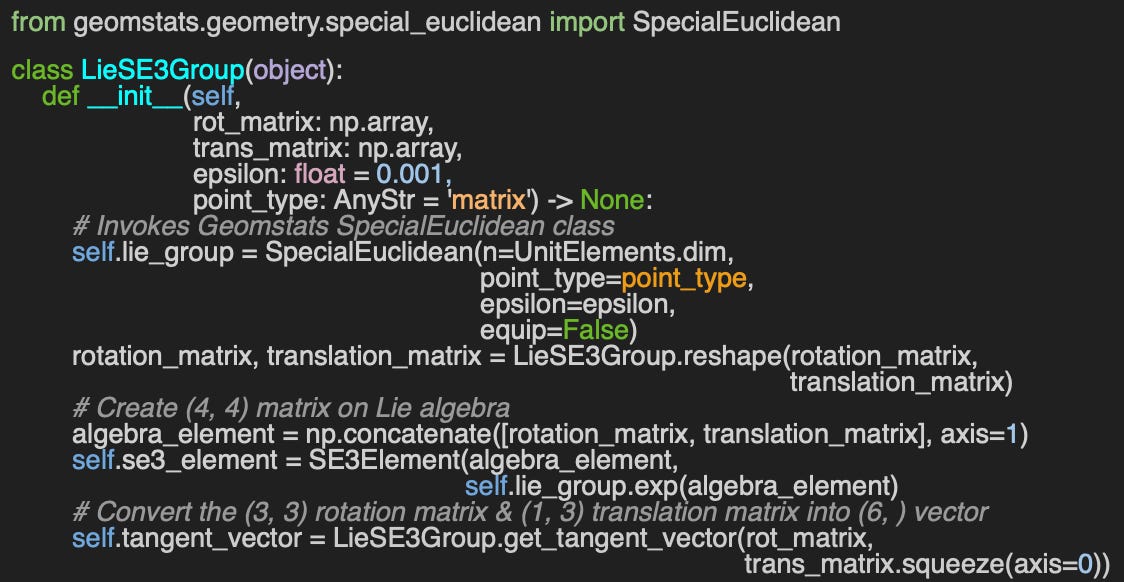

For the sake of convenience, we wrap the creation and manipulation of elements of the SE(3) into a class LieSE3Group with two constructors:

The constructor creates a new element in the SE3 manifold, using the two elements in Lie Algebra: 3x3 rotation matrix rot_matrix and 3x1 translation matrix trans_matrix. The other arguments are epsilon is the precision used for calculations involving potential division by 0 in rotations (default 1e-3) and point_type that defines the vector or matrix representation of the group.

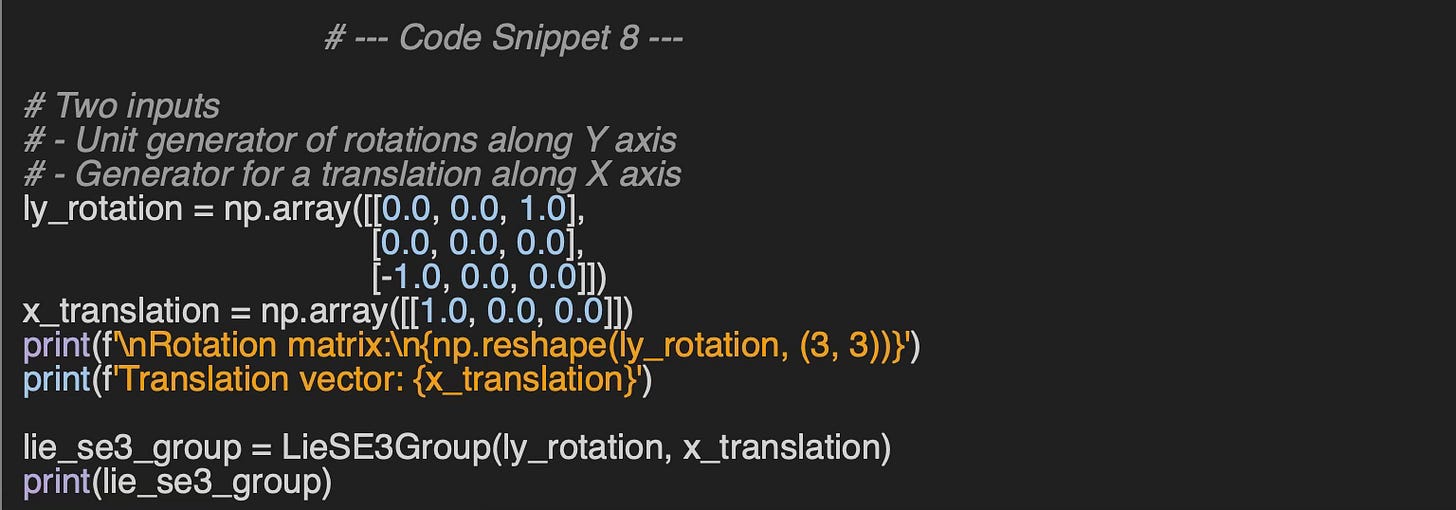

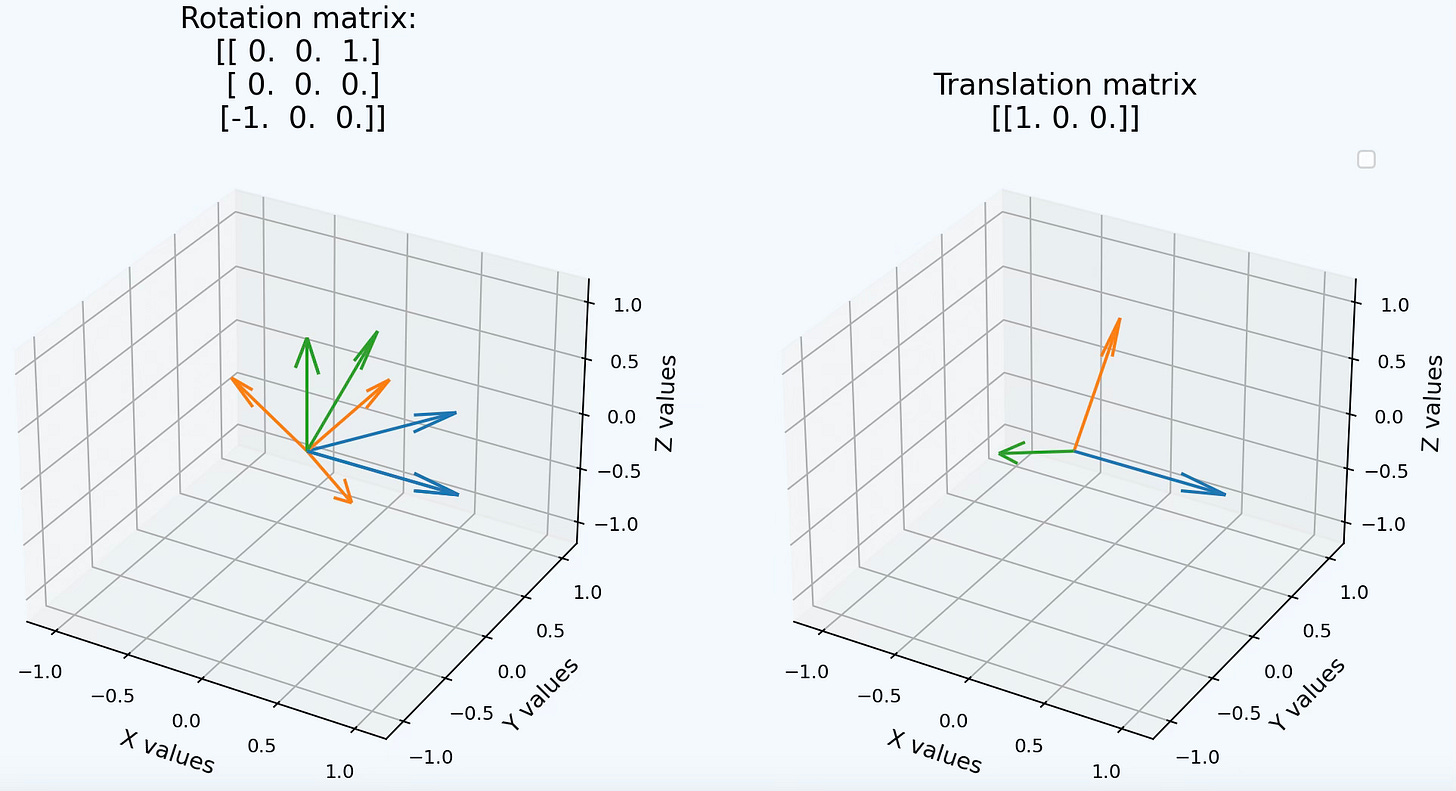

Let’s generate the element of SE3 manifold from an element combining a generator of rotation along Y axis and unit translation along X axis.

Output:

Rotation matrix:

[[ 0. 0. 1.]

[ 0. 0. 0.]

[-1. 0. 0.]]

Translation vector: [1.0, 0.0, 0.0]

SE3 algebra element:

[[ 0. 0. 1. 1.]

[ 0. 0. 0. 0.]

[-1. 0. 0. 0.]

[ 0. 0. 0. 1.]]

SE3 group element:

[[ 0.5403 0.0000 0.8414 1.5097]

[ 0.0000 1.0000 0.0000 0.0000]

[-0.8414 0.0000 0.5403 -0.6682]

[ 0.0000 0.0000 0.0000 2.7182]]Fig. 5 Visualization of Rotation Ly and translation algebra elements.

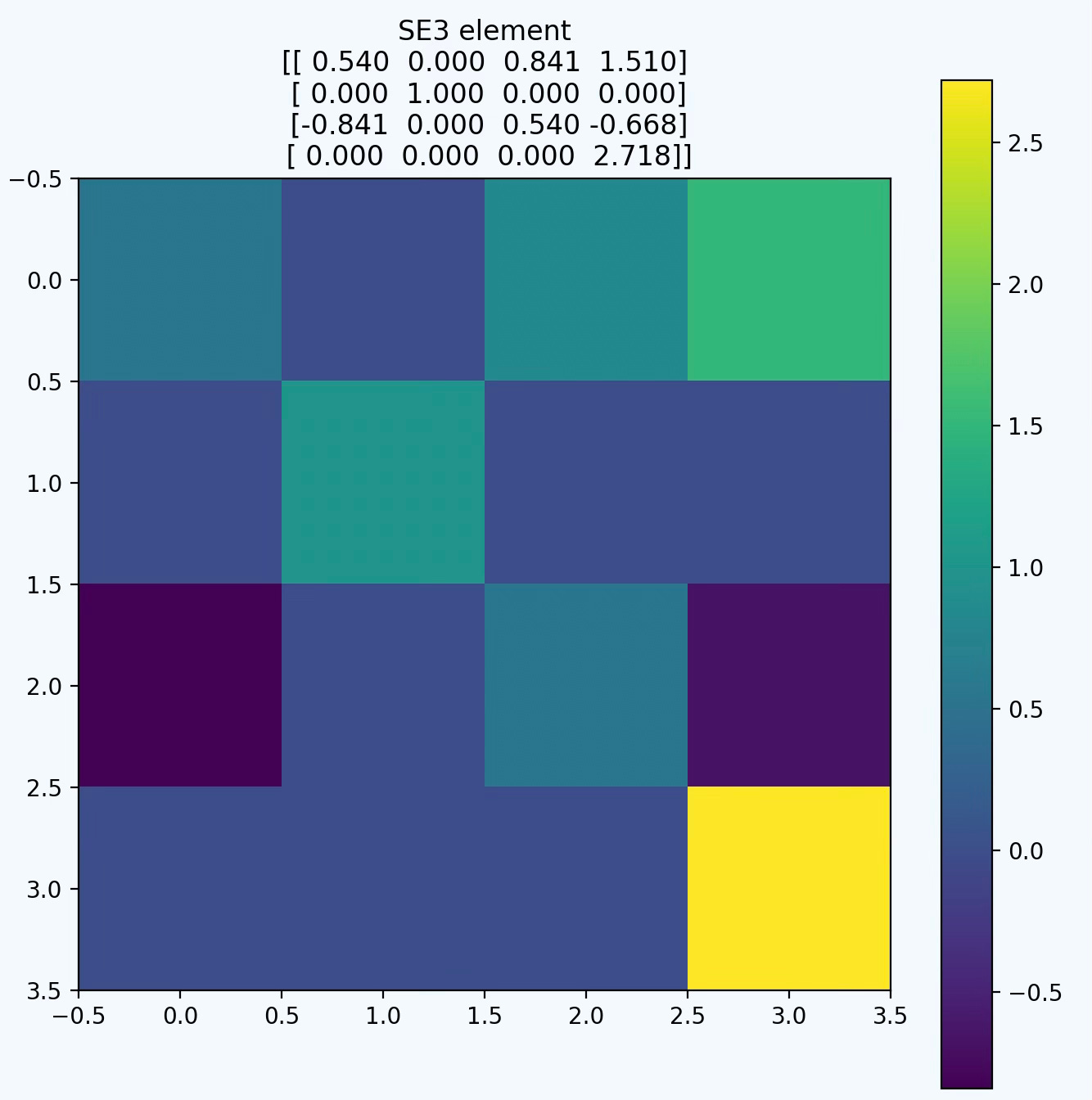

Finally, we visualize the SE3 elements as a Heatmap

Fig. 6 HeatMap visualization of a SE3 element generated from a 90 degrees rotation along Y axis and a translation along X axis

🧠 Key Takeaways

✅ Lie groups simplify manifold analysis by capturing and utilizing symmetries present in datasets.

✅ Lie algebra enables the study of complex nonlinear transformations by working with a simpler linear structure in the tangent space.

✅ The Geomstats library equips data scientists with differential geometry tools, including manifolds and Lie groups, to facilitate the development of nonlinear statistical and machine learning models.

✅ Among these, SO(3) and SE(3) are particularly well-suited for learning, as their manifold and algebraic structures can be easily visualized and interpreted.

📘 References

Introduction to Geometric Deep Learning - P. Nicolas - Substack

Introduction to Differential Geometry - J. Robbin, D. Salamon - ETH Zurich

Geometric Methods and Manifold Learning - M. Belkin - Ohio State University

Algebra, Topology, Differential Calculus, and Optimization Theory For Computer Science and Machine Learning - J. Gallier and J. Quaintance - Department of Computer and Information Science - University of Pennsylvania

Basics of Classical Lie groups: The Exponential Map, Lie Groups, and Lie Algebras University of Pennsylvania

Introduction to Lie Groups and Lie Algebras - A. Kirillov, Jr - SUNY at Stony Brook

Overview of Geomstats for Geometric Learning P. Nicolas - Substack

🛠️ Exercises

Q1: Which field(s) benefit the most from for Lie Geometry?

Q2: What are the two conditions that defines a special orthogonal group?

Q3: What is the size of a SE3 element?

Q4: Can you write a code snippet to compute the SO3 element for a 3x3 matrix representing a unit generator of rotation along Z-axis and infer its corresponding algebra element? Can you verify that the computed algebra element is almost identical to the original matrix?

Q5: Can you implement the generation of a SO3 element from a combination of 3 unit generators of rotations along X, Y and Z axes?

👉 Answers

💬 News & Reviews

This section focuses on news and reviews of papers pertaining to geometric deep learning and its related disciplines.

Paper review: Deep Learning Symmetries and Their Lie Groups, Algebras, and Subalgebras from First Principles R. Forestano, K. Matchev, K. Matcheva, A. Roman, E. Unlu, S. Verner - Physics Dept. University of Florida

Much effort in the field of machine learning is devoted to creating increasingly complex models. However, it is becoming evident that the caliber of training and validation data is crucial, aligning with the concept of Data-centric AI.

The paper discusses how defining symmetry properties in the hidden layers of a deep learning model can streamline its training and make it easier to interpret. It introduces a neural network architecture that detects and classifies symmetric patterns in a labeled training dataset.

This method utilizes group theory to:

Generate symmetry transformations that maintain the integrity of labeled data.

Pinpoint infinitesimal transformations, known as symmetry generators.

Modify the machine learning model's loss function to uncover sub-algebras (Lie algebra) of the symmetry group, which are formed as linear combinations of the symmetry generators.

Ascertain the complete symmetry group and Lie subgroups that optimize the number of generators.

Note: The paper presupposes a fundamental understanding of group theory, homogeneous spaces, and manifolds. It does not include Python code

Expertise Level

⭐ Beginner: Getting started - no knowledge of the topic

⭐⭐ Novice: Foundational concepts - basic familiarity with the topic

⭐⭐⭐ Intermediate: Hands-on understanding - Prior exposure, ready to dive into core methods

⭐⭐⭐⭐ Advanced: Applied expertise - Research oriented, theoretical and deep application

⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐ Expert: Research , thought-leader level - formal proofs and cutting-edge methods.

Share the next topic you’d like me to tackle.

Patrick Nicolas is a software and data engineering veteran with 30 years of experience in architecture, machine learning, and a focus on geometric learning. He writes and consults on Geometric Deep Learning, drawing on prior roles in both hands-on development and technical leadership. He is the author of Scala for Machine Learning (Packt, ISBN 978-1-78712-238-3) and the newsletter Geometric Learning in Python on LinkedIn.

There's a more intuitive and visualizable way to look at Lie algebras as bivector spaces in Geometric Algebra (Clifford Algebras with real-valued coefficients.) To make a Clifford algebra, take n orthonormal basis vectors for the n dimensions of the algebra, and take the product of all possible combinations of those vectors. This is the wedge, ^, or outer product (= the geometric product for orthogonal vectors such as these basis vectors); the outer product forms higher-dimensional subsopaces from lower-dimensional ones, for instance, with a pair of orthogonal vectors it forms the plane of rotation that takes the first vector onto the second vector (or times -1 to rotate the second vector on to the first, a^b = -b^a). From n orthonormal basis vectors defining n dimensions of a space, the number of basis bivectors (mutually orthogonal planes of rotation) one can form is binomial[n,2], the number of ways of choosing 2 distinct vectors from the set of n vectors. (This works for scalar, vectors, trivectors, etc., replacing "2" with the appropriate number from 0 to n, and is one of the three central axioms of Clifford algebras, along with the orthonormal basis vector rules: a^a=1 (or -1, if that is its signature), and a^b = -b^a. The kinds of blades (products of n basis vectors) that can exist are defined by the binomial axiom, and the products of any of these blades with any others can be found with the other two axioms.)

A Lie algebra is nothing but a bivector algebra, that is, a Clifford algebra working only with the bivectors, pairs of dimensions defining planes of rotation possible in the space. E.g. for 4-D, there will be a space of 6 possible planes of rotation, each with its own real-valued weight, and taking the sum of these six weighted basis bivectors gives any possible rotation in a 4-D space. (The sum of all the components is a bivector, but not a blade, it can't always be represented as the product of two vectors, unlike in lower dimensions, e.g. wx + yz is in the space of bivectors, but is not the product of any two vectors.)

By multiplying by the exponential of a bivector, one can rotate any object in the plane of the bivector, weighting the exponent to give whatever degree of rotation. Usually this is done as a "sandwiching" operation like so: e^(B/2) X e^(-B/2), with X being anything you want to rotate, including high-dimension and mixed-dimension objects, and B being a bivector [edit: a blade bivector, a product of two vectors that are not in the same direction]. This entire expression can in turn be embedded in another sandwich using a different bivector, and so on, allowing an arbitrary chain of successive rotations in arbitrary planes to be applied from innermost to outermost. This works in any dimension of any signature and is perhaps the most practically powerful use of Geometric / Clifford Algebras. Matrices are not needed.

Also, every Lie group can be represented as a spin group by using the bivector representation of its corresponding Lie algebra.